October 4, 2017

Posted by:

IEPA

Google’s new role in Early Intervention

By Sarah Hetrick.

Depressive disorders affect up to 25% of young people by the age of 18 and account for the greatest global burden of disease in young people[1].

Despite this, many young people do not seek help. It’s true that in Australia we have seen an increased focus on youth mental health [2-4]. We have also seen a doubling in the rate at which young people seek mental health treatment [5, 6]. Nevertheless, there are still large numbers of young people who are not receiving any treatment for depression [6, 7]. Untreated depression can result in disruption to academic and vocational achievement [8-10], interference with social relationships [11, 12], development of co morbidities and chronic illness [13], and is associated with greatly increased risk of suicide [14-17].

There are many potential barriers to seeking help, but a key barrier is poor mental health literacy in that young people have difficulties recognising symptoms as a mental health problem requiring intervention [18, 19].

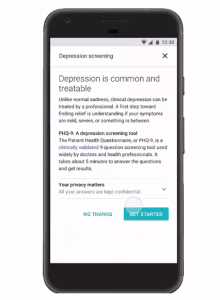

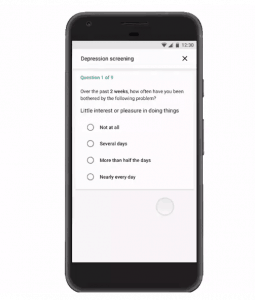

An initiative by Google, where people searching with the word ‘depression’ are directed to complete a depression screening tool, represents an important step in helping people recognise they may have depression. This tool could have a role in promoting early detection and treatment of depression. While there are many tools available online purporting to assess depression, Google have utilised the PHQ-9, which is backed by a large amount of research. The PHQ-9 has been used in young people, although Google might consider including the PHQ-Adolescent version of this measure for use in younger people [20].

What is critical in this initiative is that those who screen positive for depression online are reassured with messages of hope about the availability of effective interventions for depression, and they are provided with information about how to access these interventions.

Access to treatment remains a challenge in most countries [21], but, again, the Internet offers a solution given the rise of technology-based cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) interventions [22] that can be rolled out on a large scale.

Evaluation of Google’s initiative to measure any adverse outcomes, and the impact of the initiative on mental health literacy and help-seeking, should be embedded in Google’s venture into depression screening.

For more, follow IEPA Network on Twitter and LinkedIn.

You can also follow Sarah Hetrick on Twitter and LinkedIn.

References for further reading

Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10-24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2093-102. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60512-6.

McGorry PD. The specialist youth mental health model: strengthening the weakest link in the public mental health system Med J Aust. 2007;187:S53-S6.

McGorry PD, Goldstone SD, Parker AG, Rickwood DJ, Hickie IB. Cultures for mental health care of young people: an Australian blueprint for reform. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:559-68.

Wright A, McGorry PD, Harris MG, Jorm AF, Pennell K. Development and evaluation of a youth mental health community awareness campaign–The Compass Strategy. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(1):215.

Sawyer MG, Arney FM, Baghurst PA, Clark JJ, Graetz BW, Kosky RJ, et al. The mental health of young people in Australia: key findings from the child and adolescent component of the national survey of mental health and well-being. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry. 2001 Dec;35(6):806-14. PMID: 11990891.

Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, Boterhoven de Haan K, Sawyer M, Ainley J, et al. The Mental Health of Children and Adoelscents. Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health; 2015 August 2015.

Knapp M, Snell T, Healey A, Guglani S, Evans‐Lacko S, Fernandez JL, et al. How do child and adolescent mental health problems influence public sector costs? Interindividual variations in a nationally representative British sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(6):667-76.

Kessler RC, Foster CL, Saunders WB, Stang PE. Social consequences of psychiatric disorders, I: Educational attainment. Am J Psychiatry. 1995 Jul;152(7):1026-32. PMID: 7793438. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1026.

Kessler RC, Heeringa S, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, Rupp AE, Schoenbaum M, et al. Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Jun;165(6):703-11. PMID: 18463104. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010126.

Gibb SJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Burden of psychiatric disorder in young adulthood and life outcomes at age 30. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 2010 Aug;197(2):122-7. PMID: 20679264. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.076570.

Knapp M, McCrone P, Fombonne E, Beecham J, Wostear G. The Maudsley long-term follow-up of child and adolescent depression: 3. Impact of comorbid conduct disorder on service use and costs in adulthood. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 2002 Jan;180:19-23. PMID: 11772846.

Knapp MRJ, Scott S, Davies J. The cost of antisocial behaviour in younger people. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;4:457-73.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):593-602. PMID: 15939837. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593.

Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, Trautman P, Moreau D, Kleinman M, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Archives of general psychiatry. 1996 Apr;53(4):339-48. PMID: 8634012.

Cash SJ, Bridge JA. Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009 Oct;21(5):613-9. PMID: 19644372. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833063e1.

Foley DL, Goldston DB, Costello EJ, Angold A. Proximal psychiatric risk factors for suicidality in youth: the Great Smoky Mountains Study. Archives of general psychiatry. 2006 Sep;63(9):1017-24. PMID: 16953004. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1017.

Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. The Christchurch Health and Development Study: review of findings on child and adolescent mental health. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry. 2001 Jun;35(3):287-96. PMID: 11437801. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00902.x.

Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(1):113. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-113.

Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, Boterhoven De Haan K, Sawyer M, Ainley J, et al. The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents. Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health, 2015.

Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(3):196-204.

Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):858-66.

Pennant ME, Loucas CE, Whittington C, Creswell C, Fonagy P, Fuggle P, et al. Computerised therapies for anxiety and depression in children and young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2015;67:1-18.